Elvis Saltwater

The last three stops on our unplanned but ardently embraced Ancestral Puebloan tour, before we turned north to Utah's unexpected challenges, were Aztec Ruins National Monument, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument. At Aztec Ruins we rolled in playing Dylan's "Romance in Durango," just as we had in Durango, CO, although the song is about Mexico ("Santa Fe" was our soundtrack for dear, dear, dear, dear, dear, dear Santa Fe ,of course). "By the Aztec ruins and the ghosts of our people/hoofbeats like castanets on stone," Dylan sings, in a Mexican fantasia that incorporates pretty much every Spanish word a gringo can think of—cantina, querida, corrida, torero, tequila. The line invokes the very trope of the vanishing, spectral ancients that current Park historiography is revising (and which I wrote about in my previous post). The Native park ranger at Aztec Ruins, herself a Puebloan, talked about the change in recent years in naming practices, noting that while "Anasazi" is no longer in use, there has been no move to correct the historically inaccurate "Aztec" first applied by Spanish explorers traveling north from Mexico, who called any old ruins they saw Aztec. The face of God will appear with his serpent eyes of obsidian.

Aztec Ruins

Characteristic dark stone band—not decorative, possibly representing water

The Aztec Ruins are of a very large Great House, part of the broader "Chaco Phenomenon" of 850-1250 CE, a period of collaborative trade, cultural unity, and artistic flourishing across many hundreds of miles of the Four Corners region. It took us about 3-4 hours to drive from each of these sites to another; 1000 years ago these pueblos were all considered neighbors. The work of repointing the old stones to preserve them happens constantly, and is considered sacred work. Some of the wooden ceiling beams in Aztec Ruins are original, dating from 850. While we visited Aztec, a group of restorers from Ácoma Pueblo worked on one room in the site, listening to a boom box.

Ácoma Pueblo restorers at Aztec Ruins

Our friends Robert and Don and the artist we had talked with at Taos Pueblo, Sam Romero, had all separately spoken reverently about Chaco Canyon, which I had not visited in my childhood travels. Don said "it is remote…amazing and most worth it if you camp." This was our plan. We have been hauling our tent, oversized sleeping bags, camping unfriendly air mattresses, and cooler for our entire trip; I'd say we haven't touched them, but we have to pull them out of the trunk and back seat every time we stop in order to access our clothes and book bags and our kid's bags of books and art and weaving and crocheting supplies. We are not super experienced campers. Our grand plans to stay in campgrounds at Zion, Arches, and other national parks had been thwarted by our misrecognition of the impact of the centenary of the National Park service this summer: popular parks have been booked for many, many months, and the first-come, first-served sites have recommended arrival times of 6am, which kind of defeats the purpose of camping in a place for the night. But Chaco Canyon had a spot for us.

Driving in to Chaco Canyon

About 10 miles in on the 23-mile dirt road that forms the final half of the 40-mile access road to Chaco we became impatient with the pace of the cautious cars ahead of us. The "dirt" road was more like a wash post-flash flood, and the other vehicles were taking it very slow. We swung out around two or three cars and almost immediately hit a huge ditch hard and blew out our tire, 50 or 60 miles from the nearest service station and at least 45 miles from cellular reception. The park ranger we later consulted looked at us coolly in our slight panic, informed us that our neighboring tentsite companions also got a flat on their way in, and asked "have you really never had to change a tire before?" (Not since a tire had been slashed on Christmas Day in Philadelphia, and even then, I think my brother-in-law mostly handled it.) She said that a different ranger had blown out a tire on another road two days earlier, had driven into a ditch, found herself caught in a flash flood, and ended up with a truck filled with three inches of mud. That is a better story than receiving a punitive flat for itchy touristic driving.

Still, not a bad spot to have to change a flat

Oral history reports that the great buildings of Chaco were built by command of the Great Gambler, who came from the south and enslaved the Puebloan people before they outwitted and expelled him. Perhaps a signal of the Gambler's character can be seen in the location of the Great House: beneath a 140 foot, 30,000 ton rock known as "Threatening Rock." Chacoan builders recognized the danger of the rock, according to the park service's guide: they placed

pahos (prayer sticks) in the crevice between the rock and the cliff. They built a supporting masonry terrace below the base of the rock sometime between CE 1040 and 1050. . . . The traditional Navajo name for Pueblo Bonito is Tsé biyahnii'a'ah, which means "rock that braces and supports the structure from below," and refers to the masonry that supported Threatening Rock.

In 1941 Threatening Rock finally fell and destroyed 30 rooms in the pueblo.

The remains of Threatening Rock

Another threatening rock, 1/3 the size of the one that flattened 30 rooms in Pueblo Bonito

We put up our tent and roasted burgers and marshmallows under less threatening red rocks in the platonic ideal of campsites. We heard coyotes in the wash. We borrowed electricity from a park ranger when our car cigarette lighter adaptor didn't work on the air mattress pump in this primitive campsite. Lightning was constant over the mesa, but the sky above us was clear and we lay on our backs on the picnic table and watched the beginning of the Perseid meteor shower. J and I pulled from a whiskey bottle and our kid sniffed our clothing to take in the campfire scent. Even if we never again used the camping equipment that had taken up 70% of our car storage space on this trip, we assured each other, this evening had been worth it. In the morning we drove on our spare donut tire very very slowly out of the park, and then very very slowly to the nearest town, well over an hour away, and had a matching used tire put on the car at Kachina Tire Shop. It took five minutes.

I had been looking forward to Canyon de Chelly the most on this trip; I have the strongest childhood memories of riding through the wash to the cliff dwellings on horses led by Navajo guides. The only access to the canyon's interior, which is on Navajo Nation land, is via tribal guides (whether on foot, via jeep, or on horseback); the U.S. National Park service operates only a scenic rim drive. In this canyon beginning in 1864 Kit Carson had starved out 8000 Navajo, precipitating the Long Walk that removed the Navajo from their ancestral lands. We arranged for a three-hour horseback tour with Justin's Horse Rental, and as we pulled up to the small wooden building its rectangular frames clicked into the place that my memory had held for them for 32 years: it was the same outfitter we had used when I was 11 or 12. Justin confirmed that yes, his family's business was over 35 years in operation, and the building was at least that old. He asked what my guide's name had been; perhaps it was then-teenaged Patrick? Possibly. His cousin Dennis would be our guide, and we mounted our horses, Big Red for me, Blondie for J, and Happy for our kid. In childhood summers we had frequently done horse tours, but I had not been in a saddle since I was probably 13, when a ranch owner in the Badlands had asked me to come back the following summer to serve as a trail guide. (I had been thrilled by this offer until my father pointed out that all the girls on the ranch were about 14 or 15, and the ranch owner was a lone older man.) It was the first time riding for J and our kid.

Justin's Horse Rental, Canyon de Chelly

Dennis was a manager of Indian rodeos, and was a former bronco himself. He was working on setting up international Indian rodeos with Canadian contacts, and talked about visiting Edmonton and noticing language similarities between Navajo or Diné and First Nations tribes, much as he said was the case with the neighboring Apache reservation in the Four Corners region. Of the Hopi, whose reservation was enclosed by a section of the Navajo reservation, Dennis had little to say. "They don't understand us and I have nothing to say to them," he told us. Afterward I read up a bit on the 100+ year Hopi-Navajo land dispute, which seems to be the source of this division, and similar talk I remembered from 30 years ago.

Happy the horse had been nuzzling a colt at the headquarters, and spent our ride out whinnying loudly. "She misses her baby," Dennis told us. "When we turn back home she will know and will take off." This delighted our kid, who was thrilled with Happy's brisk pace and desire to trot. When we made the final turn the call and response of Happy and her foal and then their ecstatic reunion started tears to my eyes.

Happy and baby

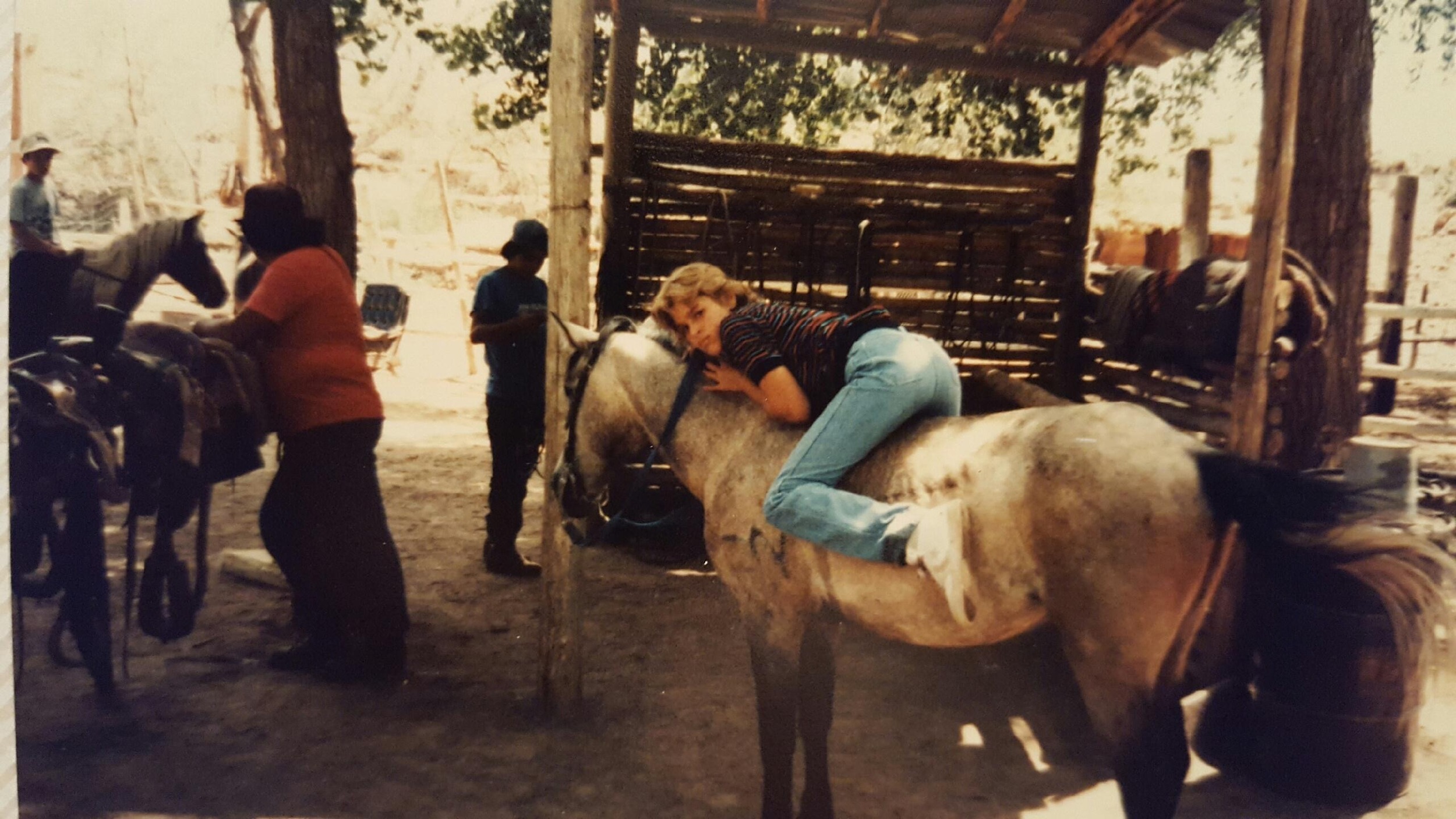

I texted my parents a picture of Justin's Horse Rental and asked my mom if she could go through the photo albums of our 1970s and 80s travels and find the picture of me sitting atop the sweating horse post-ride, 1984 or so.

Me and Cricket, 1984ish

Here my memory diverged: I had repressed from the mind picture both my painfully preteen posturing and the enormous white Converse hightops. The black striped polo I did recall. Later that night I emailed the picture to Justin Tso, the owner of the riding service, who is also a well-known painter, and asked him if he recognized any of the figures in the photo, despite the passage of decades and the turned backs of the men. I checked my email as often as northern Arizona's indifferent cellular coverage permitted. It was two days before Justin responded to my whinnying appeal for recognition and connection over the years: "Sure, Eddie Draper (orange pull-over), the late Jerry Skinner and you are on Cricket!"

Flush from our camping triumph in Chaco Canyon, and intoxicated by our hours moseying along the floor of Canyon de Chelly, we thought we would double down and pitch our tent in the park's campground near the ranger station on the bypass road, under the cottonwood trees that had been planted in Canyon de Chelly by the Civilian Conservation Corps. There were few other occupants in the campground, and when we emerged from our car into great clouds of mosquitos we understood why. J and I exchanged a long look and then drove across the bypass to the Holiday Inn Express, Chinle. There were no mosquitos on the unexpectedly posh—for a Holiday Inn—pool deck, which was lined with sunbathing women with sleek seal bodies wearing ambitious bikinis. J and I exchanged another long look: where were we? I was waiting for Van Halen's "Beautiful Girls" to start playing. When the kids splashing in the pool started shouting to each other in French, Italian, German, with the occasional mild reproof from a lounging parent ("suave"), we understood why the Holiday Inn pool scene had seemed so foreign.

As we turned toward southern Utah's superb cluster of national parks, the original ultimate goal of our road trip, we took a detour to drive through the iconic Monument Valley. After having the various sites of the Ancestral Puebloans more or less to ourselves in the previous week, we were startled to arrive at a traffic jam: a long line of cars at a standstill, occupants standing at the side of the road. They were awaiting admission to the 17-mile scenic loop through Monument Valley, which is a Navajo Tribal Park requiring admission. Where we came to a stop was near a dirt-floored shop selling jewelry and crafts, so we broke free of the line and stopped. Pinup girls from the "Women of the Navajo" calendar smiled at us from the walls. The proprietor was a jeweler with the greatest name ever: Elvis Saltwater. He is part Zuni, he told us, which explains his unusual last name. Our fiber-arts-loving kid asked him about the woven pieces for sale (which we loved and one of which we bought), and asked how different patterns were made. Elvis Saltwater gave them a mini clinic on Navajo weaving techniques, showing them pictures of looms, explaining techniques, discussing patterns. He invited them to email him with any questions. The piece we bought was woven by Elvis's 22-year-old daughter Shanythia Saltwater; our 10-year-old glowed with pleasure to hold the fruit of a fellow kid’s loom. We are now on our return drive, and our kid has spent the last two days with a small craft loom, weaving with Navajo wool they picked up in Chinle outside of Canyon de Chelly, experimenting with the patterns and techniques to which they were introduced by Elvis Saltwater. We did not rejoin the line of cars appealing for entry to Monument Valley.

Next: driven from Zion.